Are all “Walled Gardens” alike?

Even though Google continues to push out its end-of-cookies date – for lack of any adequate replacement for advertising targeting – we’ve been hearing more about the targeting data strengths and weaknesses of the big three “walled gardens” (Google, Facebook and Amazon) in the B2C space. In B2B, the concept of “walled gardens” also applies specialized publishers, but it’s less well understood. And while it’s conceptually accurate that any walled-garden proprietor who has their users’ permission could potentially offer marketers a really valuable data source, most were not conceived or designed for that purpose. The reality is that much of the so-called intent data from B2B publishers is actually an amalgam of very weak signals, leaving it up to you as B2B marketers to try and figure out the difference between a truly valuable offering and one that sounds good but can’t deliver. From where I sit, I can see at least 3 important shortcomings to be aware of:

- Business models designed for broad and shallow: Most online publishers were built on a model designed to maximize advertising dollars from big spenders. Think about a publication like USA Today: You get the most eyeballs by covering a lot of topics at a very high level.

- Anonymous behavioral signals are not additive: Despite the reality that two weak signals here don’t add up to a strong (do you remember the fallacy of packaging bad mortgages together and rating them good?) many providers are doing this and saying it works.

- “Directional” suggestions from marketing don’t deliver real value to sales: Not only are MQA’s subject to serious false-positive issues, when a supplier pairs MQAs with cold contacts – think about it – it’s really no better than having a prioritized territory account list and doing cold calling.

To provide you with better insight on the right intent data for your needs, I’ll be discussing these at length using some current examples that are out there.

Most publishers were built on an advertising-driven business model

Most publisher walled gardens were built for advertising purposes, not to deliver the kind of high-quality purchase intent data necessary to greatly increase sales efficiency. This advertising-based business model compelled them to seek out the broadest possible audiences within large, general interest categories. Even in quasi-specialty categories (like “tech”), broad and shallow coverage was the best way to maximize ad dollars by covering a little about a whole lot.

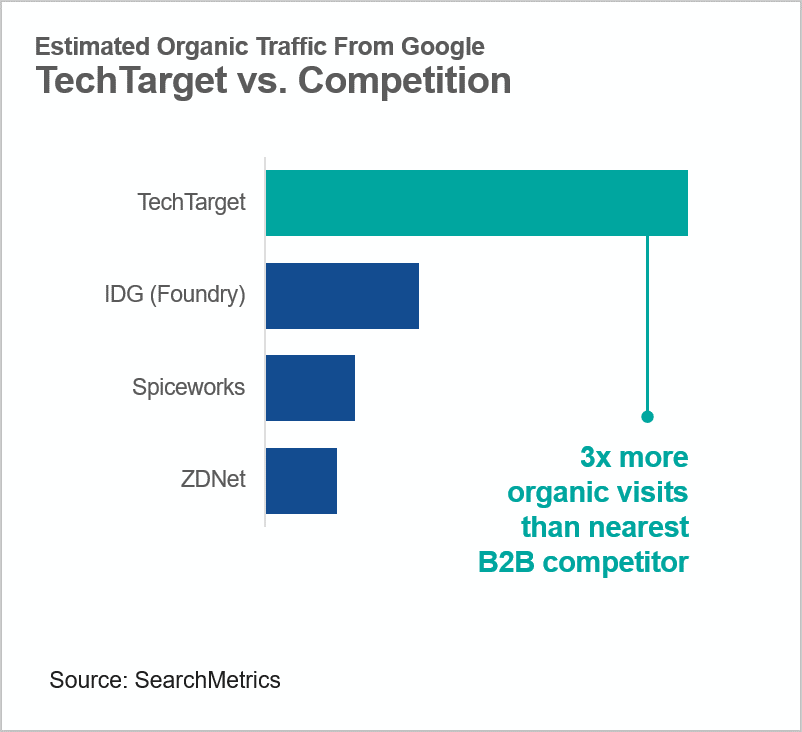

In enterprise tech, there are a handful of large walled gardens that on the surface appear similar but are actually very different from a business model, data, and value delivery perspective. IDG (now Foundry), SWZD (Spiceworks ZiffDavis), Informa (who bought UMB), CNET, et al are all examples of the old-school advertising-driven business model. As a result, they can’t deliver the precision for real Intent revenue impact. In contrast, TechTarget was purpose-built for the internet era and the very granular decision support needs of enterprise tech buyers and sellers. Evidence of the fundamental differences between the models can be seen in their respective organic search rankings on Google: TechTarget’s micro-segmented approach results in far more total organic traffic (it’s grown some 2X in just the past two years) and much more granular segmentation capabilities. For you as an advertiser, that’s good for targeted contextual advertising (versus spray and pray programmatic). It’s even better for Intent data precision, lead conversion yields, opportunity identification, and a host of other sales and related go-to-market needs. Let’s take a closer look at why.

Broad and shallow can’t get you to precision intent data

If you’ve built your publishing model to attract very broad audiences, like say a ComputerWorld or InformationWeek has, the whole concept is to build a news-oriented media property that people can get a broad gist of “what’s happening” out there. It’s a model that helps you sell advertising in big chunks to big spenders, which is efficient for you, but unfortunate for more specialized advertisers with specialized targets and less budget. Even today, this model may still be “working” for marketers at the very biggest companies, because they can afford to advertise at tremendous scale. But despite the low cost of programmatic advertising, smaller brands need a lot more granularity to have any hope of impacting their laser-focused niches. They need to reach those people who really care about innovative differentiators, not everyone who has a passing interest in a huge category like “Security” or “Cloud”.

Unfortunately for broad-based legacy publishers, the advertising-focused business model actually precludes a pivot to a more insight-rich approach. Here’s why: Since their whole business model revolved around advertising, it’s actually not constructed to be able to generate the granularity required to deliver precision Intent data. By design, this business model sits on an infrastructure built for generalities and scale, not for hyper-segmented accuracy and detail. By design, the editorial content and reportorial staff skills don’t aim to serve the highly specific needs of tech decision-driving professionals (whose input is required in every significant enterprise tech purchase). At best, these types of publishers can only track wide account behavior surges in the broadest most general sense of the idea. They can only see broad interest trends. Which means, from the traffic they do get, they can only supply high-level data, generating insights too vague to be meaningfully useful for anything other than high-level advertising. In contrast, TechTarget’s approach was built for granularity from the start, so our model is not only extremely efficient for advertising, it’s incredibly powerful for sales. It has the granularity about an individual prospect’s needs and more that enable a seller to personalize their outreach.

How should you factor this into your understanding of the Intent data space as a whole?

Some will argue that nearly any legitimate source of B2B targeting data is an improvement on basic programmatic ad targeting (after all, it’s an adtech category struggling with nearly $65 billion in fraud annually – 50%+ of total spend!) And maybe if all you want to do is target your digital advertising a little better, such legacy-model tech publishers can improve on even broader B2B outlets like Forbes, WSJ.com and the rest. The point I want you to be very clear on here is that the Intent market is full of self-proclaimed “Intent data” providers – outlets that obtain their data in all sorts of ways – but because of fundamental flaws in their business models (similar to those of the legacy publishers), few of them can actually help you make substantive progress on your most pressing business objectives.

What you should understand about weak Intent + cold contact data

As Intent started to draw attention, many data providers rushed to offer additional “Intent” feeds on top of the contact information that is their bread and butter. Finding themselves with gaps in both areas (contacts and Intent), many legacy publishers have pursued this approach as well, through a combination of point-solution acquisitions and both 2nd and 3rd party external sourcing. After cobbling together a solution, such approaches now lead publishers to say things like: [We now provide] “multiple intent sources combined to capture buying behavior”, even though that doesn’t add up. They make claims that are hard to understand like: [We] “capture the signals that drive buying decisions … and layer intent signals from diverse buying channels”. My belief is that potential buyers like you should be careful to parse such verbiage very carefully. Let’s discuss some of the issues in more depth:

Many providers say they layer in data from the “public web”, but that data is public precisely because it has little precision targeting value. The content that generates it is either too general, too widely available or both. This turns out to be the fundamental weakness of both advertising-based publisher data and all 3rd party Intent alike: it’s derived from low value original sources. Furthermore, unlike with contact data where different sources added together can help clean up missing fields or verify latest known account affiliations, weak sources of intent data can’t be strengthened like this. Most accounts are big, diverse groups of anonymous people generating lots of different signals all the time. If you don’t know much about the signals or who they’re from, you can’t determine if they are truly additive. Thus instead of actually strengthening the signal, if you do this with behavioral data, you’re often just layering two false positives on each other.

A lot of providers talk up their selection of “Industry content”. But any B2B and lots of B2C properties cover “industry” stories. Unless that content’s been built to help differentiate between highly granular topics, it can’t actually support the highly specific information requirements and concerns of enterprise tech buying teams. And thus, as a marketer, you can’t actually tell if their needs are relevant to what you sell. Like many Intent providers, legacy publisher-style data can neither differentiate between false-positive surges nor help buyers navigate within the highly complex, highly differentiated solution areas inside big categories like Cloud, Security, DevOps, and so on.

Many publishers are talking more about their “Opted in” audiences. While that’s good in theory, in practice, in order for it to be valuable to you, you need to have the behavior of this specific person. If the behavior is only available at the account level, it tells you nothing about any specific contact. When the behavioral data being tracked is general-interest oriented, and only at the account level, then it makes you as a marketer essentially no better off than you continue targeting your efforts on role and function alone.

Some legacy publishers specifically recognize the challenges they face and openly describe their attempts to overcome it with messaging like this: [We’ve] “matched [our account intent] to the buying team at the contact level”. I had to read this one closely, and you should too. Here, they’re actually explaining that they don’t have precision intent about those opt-in people they mentioned, so instead, they’re supplying cold contacts that they think you might want to try. This is super common now in the buyer-beware Intent space. Many of the “pop-up” intent players are offering exactly the same thing, because they can buy both surge data and contact data, massage it together, and make it sound special to you. If you were to buy in, rather than helping your sales colleagues, you’d be asking them to spend substantial energy sorting through all these cold names using expensive, brute force sales development resource. This is the exact situation that Forrester has described at length in discussing the inherent weaknesses in the MQA (marketing qualified concept).

You can see these weaknesses clearly by looking closely at flashy generic web demos

While it’s fundamentally a good idea to offer a demonstration of your product on the web, a bad generic demo can actually hurt. Coming from the enterprise tech perspective, I’ve experimented with a variety of Intent providers’ on-page demos and have not been impressed. In most, a look at the topic drop down actually illustrates many of the shortcomings we’ve been discussing. I immediately notice that the topic choices are super-limited, i.e. not granular enough to help. They can’t provide insights that differentiate between solutions and they show duplicate accounts that are supposedly in market across many categories. This is again because the data they’re using comes from an editorial model that is too broad and shallow (whether it’s their own data source or a feed that they are reselling). I’ve noticed frequently that, even when these sites claims tech expertise, their choices go no deeper than whole categories of software. What I want is the real people within accounts who care about the real differences between particular solutions. What they give me instead is a list of companies to go after that’s actually worse than if I used ICP targeting based on firmographics alone. In a number of these demos, it even seems as if the data model is based simply on a top-level extract from G2 or TrustRadius’ category definitions, leaving out all the actual value in those providers’ deeper features!

Choosing the best Intent data source for your company and use cases

Like some other newer RevTech categories, Intent data has generated a ton of interest quickly, first among marketers and more recently with sellers and other members of the GTM organization. Naturally, this attracted a host of new supplier entrants, which has complicated things for practitioners like you. Unlike late entrants, TechTarget was an early pioneer in the space because we had a data foundation that works for our clients: Our business model was specifically conceived to serve the granular decision support needs of tech buyers (and the vendors looking to sell to them). Our Priority Engine™ platform leverages a uniquely powerful, transparent 1st party “walled garden” methodology (2nd party to you) to deliver the highest quality, most actionable insights available. For additional information and to fully understand what your company can gain from precision intent data that you can’t get anywhere else, please arrange a demonstration customized to your specific needs.